This action acts, perhaps, as a coda to the long ongoing dispute between John Schey and Ruth Schey (the Scheys), Trustees of the 70 Bubier Road Trust (the Trust), owners of 70 Bubier Road in Marblehead, and the various owners of the abutting property at 74 Bubier Road and 76 Bubier Road. The 74 and 76 Bubier Road properties had been owned by Wayne Johnson. He divided the parcels and conveyed 76 Bubier Road to the defendants Robert Clark and Leslie Clark (Clarks) in 1995. Between 1995 and 2012, the Scheys and Johnson engaged in extended litigation that resulted in Johnson's house on 74 Bubier Road being torn down. The 74 Bubier Road property was foreclosed upon by defendant U.S. Bank, N.A. (U.S. Bank), which then conveyed the 74 Bubier Road property to the Clarks.

The Trust now claims that it has established a prescriptive easement to pass over part of the 74 Bubier Road property. The Clarks have moved for summary judgment; the Trust has not disputed any of the facts alleged by the Clarks and supported by the materialsdocuments, depositions, and the likein their record appendix. As set forth below, the motion for summary judgment is allowed for two reasons. First, based on these undisputed facts, the Trust cannot show facts sufficient to establish a prescriptive easement over 74 Bubier Road. Second, the Trust's position in this action is the polar opposite of the position the Scheys took in the previous action against Johnson, giving rise to the judicial estoppel of the Trust's prescriptive easement claim.

Procedural History

The Trust's complaint (Complaint or Compl.) was filed on March 6, 2017. The Answer of U.S. Bank, N.A. was filed on March 22, 2017. The Answer of Defendants Robert Clark and Leslie Clark was filed on March 29, 2017. U.S. Bank's Motion for Summary Judgment and the Memorandum of Law in Support of U.S. Bank's Motion for Summary Judgment were filed on October 13, 2017. On November 30, 2017, U.S. Bank's Motion for Summary Judgment was allowed and all claims against U.S. Bank were dismissed without prejudice. On January 5, 2018, the Motion for Summary Judgment of Defendants Robert Clark and Leslie Clark (Motion for Summary Judgment), Statement of Material Facts as to which there is no Genuine Issue to be Tried in Support of Motion for Summary Judgment (Statement of Facts or SOF), Record Appendix of Exhibits to Motion for Summary Judgment of Defendants Robert Clark and Leslie Clark (Appendix or App.), and Memorandum of Law in Support of Motion for Summary Judgment of Defendants Robert Clark and Leslie Clark were filed. On February 6, 2018, the Plaintiff's Memorandum in Opposition to Defendant's Motion for Summary Judgment was filed. The court heard the Motion for Summary Judgment on February 21, 2018, and took the matter under advisement. This Memorandum and Order follows.

Summary Judgment Standard

Generally, summary judgment may be entered if the "pleadings, depositions, answers to interrogatories, and responses to requests for admission . . . together with the affidavits . . . show that there is no genuine issue as to any material fact and that the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law." Mass. R. Civ. P. 56(c). In viewing the factual record presented as part of the motion, the court draws "all logically permissible inferences" from the facts in favor of the non-moving party. Willitts v. Roman Catholic Archbishop of Boston, 411 Mass. 202 , 203 (1991). "Summary judgment is appropriate when, 'viewing the evidence in the light most favorable to the nonmoving party, all material facts have been established and the moving party is entitled to a judgment as a matter of law.'" Regis College v. Town of Weston, 462 Mass. 280 , 284 (2012), quoting Augat, Inc. v. Liberty Mut. Ins. Co., 410 Mass. 117 , 120 (1991).

Undisputed Facts

The Trust did not oppose or otherwise dispute the Clarks' Statement of Facts, which is amply supported by the materials in the Appendix. Based on the pleadings, the undisputed Statement of Facts, and the documents and materials in the Appendix, the following facts are undisputed:

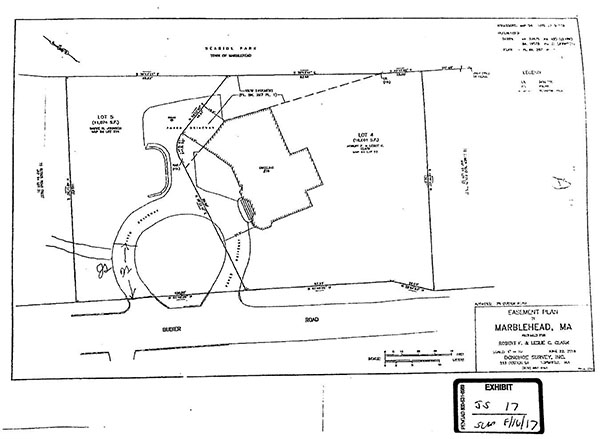

1. The Trust claims an easement by prescription over land owned by the Clarks which consists of a section of the circular driveway servicing the Clarks' home and a narrow strip of land which abuts the driveway (disputed area). The disputed area was identified on a plan by John Schey at his deposition, which is attached here for reference as Exhibit A. SOF ¶ 1; App. Exh. F.

2. The Scheys acquired 70 Bubier Road, Marblehead, Massachusetts on July 17, 1992. SOF ¶ 2; App. Exh. U.

3. In 1992, Wayne Johnson (Johnson) owned the land immediately to the south of 70 Bubier Road. SOF ¶ 3.

4. At some time after 1992 Johnson divided his land into two lots, known as 74 and 76 Bubier Road, and on February 23, 1995, sold 76 Bubier Road to the Clarks. SOF ¶ 4; App. Exh. V.

5. From 1995 through 2012, the Scheys were in involved in litigation with Johnson seeking and eventually securing removal of a house Johnson illegally constructed at 74 Bubier Road. SOF ¶¶ 11-20; see Schey v. Johnson, Land Ct. Misc. Case No. 95 MISC 221634; 8 LCR 142 (May 10, 2000).

6. Johnson owned 74 Bubier Road until his mortgagee foreclosed the mortgage on the property and subsequently sold 74 Bubier Road to the Clarks on June 9, 2017. SOF ¶¶ 9-10.

The Scheys' use of the disputed area:

7. On a single day some time during 1992 furniture was moved into the Scheys' house, at 70 Bubier Road, via the disputed area. SOF ¶ 24; App. Exh. B, pp. 49-51.

8. On a single day in 1992, 1993, or 1994 a piano and a freezer were delivered to the Scheys' house via the disputed area. SOF ¶ 25; App. Exh. B, pp. 49-51

9. Between 1992 to 1995, Britton Zitin, a child who lived across the street from 70 Bubier Road, visited with the Scheys' daughter Naomi and used the disputed area to play with Naomi in the Scheys' house or backyard. SOF ¶ 26; App. Exh. A, pp. 74-76.

10. Some evenings from 1992 to 1996, a neighbor, Abigail Zitin, babysat the Schey children and accessed the Scheys' house via the disputed area; if the babysitting was in the evening, John Schey walked Abigail Zitin home via the disputed area as well. SOF ¶ 27; App. Exh. A, pp. 75-76.

11. The Scheys' son Jonah babysat for the Clarks on a few occasions between 2002 and 2005 and accessed the Clarks' house via the disputed area. SOF ¶ 29; App. Exh. A, p. 103, Exh. B, p. 57.

12. During the summer of 2007 a Swarthmore College student stayed with the Scheys and used the disputed area to come and go. SOF ¶ 30; App. Exh. A, pp. 84-86.

13. On two separate days in 2008 or 2009 living room sofas were delivered to the Scheys' house via the disputed area. SOF ¶ 31; App. Exh. A, pp. 41-43, 46.

14. Reardon Construction (Reardon) performed substantial repairs on the Scheys' house from January 2008 through April 2009, during which time Reardon used the disputed area to deliver construction materials to the Schey house. SOF ¶ 32; App. Exh. A, pp. 45, 50-53, 55- 58.

15. From January of 2008 through April 2009, the Scheys moved out of their home at 70 Bubier Road while Reardon was performing repair work. App. Exh. A, pp. 52-54.

16. Guests of the Scheys attended a catered party in May 2009, accessing the Scheys' house via the disputed area. SOF ¶ 33; App. Exh. A, pp. 73-74.

17. On two occasions in 2010 tables were delivered to the Scheys' house via the disputed area. SOF ¶ 34; App. Exh. A, pp. 41, 43, 46.

18. On a day in 2012 chairs were delivered to the Scheys' house via the disputed area. SOF ¶ 35; App. Exh. A, pp. 40-44.

19. Reardon remodeled the Scheys' house from June 2012 to May 2013 and used the disputed area to deliver construction materials. SOF ¶ 38; App. Exh. A, pp. 53-54, 57.

20. On a single day in 2013 a ping-pong table was delivered to the Scheys' house via the disputed area. SOF ¶ 39; App. Exh. A, pp. 52-53.

21. Guests of the Scheys attended a catered party in June 2013, accessing the Scheys' house via the disputed area. SOF ¶ 40; App. Exh. A, pp. 73-74.

22. Reardon performed repair work on the Scheys' house for two months in 2014, and used the disputed area to deliver construction materials. SOF ¶ 41; App. Exh. A. pp. 54-56.

23. Reardon performed repair work for the Scheys for one month during 2015, and used the disputed area to deliver construction materials. SOF ¶ 42; App. Exh. A, pp. 54, 56-57, 59.

24. Reardon used the disputed area for four days in 2016 to deliver construction materials. SOF ¶ 43; App. Exh. A, pp. 56-57, 59.

25. There have been about six other instances of appliances being delivered to the Scheys' house, via the disputed area, since they moved there in 1992. SOF ¶ 45; App. Exh. A, p. 47.

26. On two occasions each year from approximately 1992 to 2008, at least two employees of the Scheys' medical practice used the disputed area to access the Scheys' house for an annual meeting and an annual summer office party. SOF ¶¶ 46-47; App. Exh. A, pp. 68-72, 102.

27. From 2008 to the present an employee of the Scheys who is handicapped used the disputed area to enter the Scheys' house for the summer office party. SOF ¶¶ 46-47; App. Exh. A, pp. 68-72, 102.

28. The gardener who cares for both the Clarks' and Scheys' properties cuts the grass in the disputed area. SOF ¶ 50; App. Exh. A, pp. 79-80.

29. An arborist annually walks in the Scheys' yard which takes him to the portion of the driveway in the disputed area. SOF ¶ 51; App. Exh. A, pp. 80-81.

30. A rodent prevention company services the Scheys' home three times each year and has occasionally accessed the disputed area. SOF ¶ 53, App. Exh. A, p. 83.

31. Johnson gave Reardon permission to use the disputed area to deliver construction materials. SOF ¶ 54; App. Exh. E, pp. 21-22.

Discussion

The Trust claims that it has established an easement by prescription for the use of the disputed area. The Clarks move for summary judgment arguing that either (1) the Trust cannot establish a prescriptive easement or (2) the Trust's claim of a prescriptive easement is barred by the doctrine of judicial estoppel.

Prescriptive easement.

To establish a prescriptive easement, a party must prove open, notorious, adverse, and continuous or uninterrupted use of the servient estate for a period of not less than twenty years. G.L. c. 187, § 2; Ryan v. Stavros, 348 Mass. 251 , 263 (1964); Houghton v. Johnson, 71 Mass. App. Ct. 825 , 835 (2008); Long v. Woods, 22 LCR 416 , 420 (2014). Whether the elements of a claim for a prescriptive easement have been satisfied is a factual question, and the party who claims a prescriptive easement bears the burden on every element. Denardo v. Stanton, 74 Mass. App. Ct. 358 , 363 (2009); Boothroyd v. Bogartz, 68 Mass. App. Ct. 40 , 44 (2007). These elements are discussed in turn.

The purpose of the requirement of open and notorious use is to ensure that the true owner has notice of a claim of right being made over his property and to give the true owner a "fair chance" to protect her property interests. Foot v. Bauman, 333 Mass. 214 , 218 (1955); see

Lawrence v. Concord, 439 Mass. 416 , 421 (2003). For a use to be open there cannot be an attempt to conceal the use. White v. Hartigan, 464 Mass. 400 , 416 (2013); Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 44. For a use to be notorious, the use "must be sufficiently pronounced" so a landowner who exercises a reasonable degree of supervision over the property will either directly or indirectly be made aware of the use. Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 44. It is not necessary that the use be actually known to the owner for the use to be notorious. Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 44. The use must, however, be of such a character that the true owner is put on constructive notice of the use. Lawrence, 439 Mass. at 421 (noting there is no requirement that the true owner be given explicit notice of adverse use); Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 44. When the true owner has actual knowledge of a use being made under a claim of right, the open and notorious element will be satisfied. White, 464 Mass. at 417.

To be adverse the use must be made under a claim of right and the true owner must not have given permission for or consented to the use. White, 464 Mass. at 418; Houghton, 71 Mass. App. Ct. at 835; Johnson v. Falmouth Planning Bd., 19 LCR 104 , 110 (2011), aff'd sub nom Johnson v. Santos, 81 Mass. App. Ct. 1125 (2012). Permission is not the same as acquiescence. Houghton, 71 Mass. App. Ct. at 836, quoting Ivons-Nispel, Inc. v. Lowe, 347 Mass. 760 , 763 (1964). Permission gives an individual the right to do some act on the land. Spencer v. Rabidou, 340 Mass. 91 , 93 (1959). Permission is revocable and will defeat a claim for a prescriptive easement. Houghton, 71 Mass. App. Ct. at 835. Whether permission has been granted or can be implied will depend on the particular circumstances of the case, including, among other relevant factors, the actions of the owner, the character of the land, the use of the land, and the nature of the relationship between the parties. Totman v. Malloy, 431 Mass. 143 , 145-146 (2000); Kendall v. Selvaggio, 413 Mass. 619 , 624-626 (1992); Houghton, 71 Mass. App. Ct. at 842-843. An unexplained use of an easement for twenty years creates a presumption of adversity. Truc v. Field, 269 Mass. 524 , 528-29 (1930); Houghton, 71 Mass. App. Ct. at 836, quoting Ivons-Nispel, 347 Mass. at 763. The true owner can overcome the presumption by offering evidence that explains the use or shows control over the use. Id. For example, the true owner can defeat the presumption by showing there was express or implied permission or the use was the result of "some license, indulgence, or special contract." White v. Chapin, 94 Mass. 516 , 519-520 (1866).

The adverse, open and notorious use of the land must have been continuous for no less than twenty years. G.L. c. 187 § 2; Ryan, 348 Mass. at 263. Circumstantial evidence may be used to establish a continuous use. Bodfish v. Bodfish, 105 Mass. 317 , 319 (1870); Long, 22 LCR at 420; Bagley v. Senn, 19 LCR 6 , 12 (2011). Continuous use does not mean constant use; a claimant need not show there was daily, constant or un-interrupted use over the entire twenty- year period. Kershaw v. Zecchini, 342 Mass. 318 , 320-321 (1961); Bodfish, 105 Mass. at 319; Bagley, 19 LCR at 12. Intermittent or occasional use, however, is not continuous, Boothroyd, 68 Mass. App. Ct. at 45, and sporadic use will not be found to be continuous unless the acts are "sufficiently pervasive." Pugatch v. Stoloff, 41 Mass. App. Ct. 536 , 540 (1996); Lally v. Murphy, 21 LCR 315 , 318 (2013). Regular seasonal or periodic use may be considered continuous if there is a pattern of regularity or some degree of consistency in the use. Mahoney v. Heebner, 343 Mass. 770 , 770 (1961) (seasonal absence does not prevent a finding of continuous use); Kershaw, 342 Mass. at 320-321 (finding continuous use in an adverse possession case where a circus performer had marked a boundary, cleared brush, and periodically used the property for exercises and stunts); Stagman v. Kyhos, 19 Mass. App. Ct. 590 , 593 (1985) (noting pattern of regular use on weekends).

A claimant who has not made continuous use of the property for twenty years may satisfy the statutory period by tacking on "several periods of successive adverse use by different persons provided there is privity between the persons making the successive uses." Ryan, 348 Mass. at 264; Denardo v. Stanton, 16 LCR 141 , 144 (2008), aff'd 74 Mass. App. Ct. 358 (2009). Privity exists when "use by the earlier user can fairly be said to be made for the later user, or there must be such a relation between them that the later user can be fairly regarded as the successor of the earlier one." Ryan, 348 Mass. at 264.

The Clarks dispute the Trust's prescriptive easement claim on the grounds that the use was permissive and otherwise was intermittent or sporadic. The Clarks argue that on the facts, undisputed by the Trust, the Clarks are entitled to summary judgment because the Trust is unable to establish a prescriptive easement as a matter of law. See Kourouvacilis v. General Motors Corp., 410 Mass. 706 , 716 (1991) ("a party moving for summary judgment in a case in which the opposing party will have the burden of proof at trial is entitled to summary judgment if he demonstrates

unmet by countervailing materials, that the party opposing the motion has no reasonable expectation of proving an essential element of that party's case").

The Scheys' adverse use of the disputed area began, at the earliest, in 1992, when they acquired 70 Bubier Road. Based on the undisputed facts, from 1992 through the present, the Scheys' use of the disputed area has been sporadic and intermittent. The disputed area, which was traversed by the Scheys and their guests or workmen from time to time, was used only intermittently at times when it would be opportune to do so. Across any span of 20 years between 1992 and the present there is no regular pattern of use, seasonal or otherwise, which would support finding an easement by prescription. The undisputed facts show narrow periods of regular use, such as that of the Swarthmore student in the summer of 2007, and use by Naomi Schey and Britton Zitin from 1992 to 1995. However, the overall use of the disputed area can best be described as opportunistic; that is, the Scheys used the area when it suited them but with no pattern or regularity. Compare Stagman, 19 Mass. App. Ct. at 593 (pattern of regular parking on weekends constitutes continuous use). To the extent that from 1992 to the present there have been repeated uses of the disputed area for various deliveries and to allow disabled persons access to the Scheys' home, these uses, while recurring, are not regular or unique to a season such that nonuse for the remaining majority of the year is excusable. Compare Mahoney, 343 Mass. at 770; Kershaw, 342 Mass. at 320-321. The uses claimed by the Trust are too intermittent and irregular to satisfy the Trusts burden of proving that their use of the disputed area was continuous and uninterrupted for 20 years. The Trust's claim of a prescriptive easement must fail for a lack of continuity of the use.

Further, it is undisputed by the Trust that Johnson, the owner of the disputed area at the time, gave the Reardon workmen permission to use the disputed area to deliver construction materials. While Johnson, in his cited affidavit, does not explicitly state when the permission was given, the record indicates that Johnson's home was removed in 2012. Taking judicial notice of the docket from the earlier litigation, see Schey v. Johnson, Land Ct. Misc. Case No. 95 MISC 221634, Docket Entry (Dec, 21, 2011), it is apparent that Johnson leased a new residence in early February 2012, and removal of Johnson's house was ordered to begin on February 17, 2012, continuing on "each succeeding workday without interruption, weather permitting." Id. This means that Johnson was not at 74 Bubier Road during 2012 after his house was torn down. Therefore, necessarily, the permission Johnson described was given in 2008 or 2009, which would interrupt any formulation of the 20 year prescriptive period. Houghton, 71 Mass. App. Ct. at 835. Even drawing an inference (one that is not supported by the undisputed facts) that Johnson was present on 74 Bubier Road at some time months after his house was removed and then gave permission to the Reardon workmen, that would place the permission nearly coincident with the earliest possible running of the 20 year prescriptive period. Either conclusion places a grant of permission, fatal to a claim of easement by prescription, within the bounds of the prescription period.

The Trust has not disputed the facts presented by the Clarks and on those undisputed facts the Scheys' uses of the disputed area are too intermittent and irregular to give rise to a prescriptive easement. Moreover, the Trust does not dispute that Johnson gave Reardon permission to use the disputed area. The Trust is unable to prove all the essential elements of a prescriptive easement as a matter of law. See Kourouvacilis, 410 Mass. at 716. Summary judgment shall enter in favor of the Clarks on the Trust's prescriptive easement claim.

Judicial Estoppel

The Clarks further argue that the doctrine of judicial estoppel bars the Trust from claiming a prescriptive easement, which according to the Clarks is a position incompatible with one previously taken by the Trust in earlier litigation. "'Judicial estoppel is an equitable doctrine that precludes a party from asserting a position in one legal proceeding that is contrary to a position it had previously asserted in another proceeding.'" Otis v. Arbella Mut. Ins. Co., 443 Mass. 634 , 639-634 (2005) quoting Blanchette v. School Comm. of Westwood, 427 Mass. 176 , 184 (1998). The Clarks argue that the Trust is estopped from asserting uses of the disputed area amounting to a prescriptive easement because in a 2008 affidavit, filed in the previous land court case, John Schey averred that the Scheys' front door, which leads to the disputed area, was almost never used after Johnson built his house in 1996. See App. Exhs. P, R, W.

"Because of its equitable nature, the 'circumstances under which judicial estoppel may appropriately be involved are probably not reducible to any general formulation of principle.'" Otis, 443 Mass. at 640, quoting New Hampshire v. Maine, 532 U.S. 742, 750 (2001). "However, two fundamental elements are widely recognized as comprising the core of a claim of judicial estoppel. First, the position being asserted in the litigation must be 'directly inconsistent,' meaning 'mutually exclusive' of, the position asserted in a prior proceeding." Id. at 640-641, quoting Alternative Sys. Concepts, Inc. v. Synopsys, Inc., 374 F.3d 23, 33 (1st Cir. 2004). "Second, the party must have succeeded in convincing the court to accept its prior position." Id. at 641. "Where the court has found in favor of that party's position in the prior proceeding, 'judicial acceptance of an inconsistent position in a later proceeding would create the perception that either the first or the second court was misled.'" Id., quoting New Hampshire, 532 U.S. at 750 (internal quotation omitted).

In this case, John Schey's position that the door leading to the disputed area was almost never used after 1996 is inconsistent with the claim of prescriptive easement now asserted in this action. The court therefore considers whether and to what extent the court in the previous action accepted John Schey's previous position. The Trust argues that John Schey's statement regarding the nonuse of the door to the disputed area is a detail buried among details, which did not affect the outcome in the prior litigation. A review of the orders issued in the previous case where the substance of the 2008 affidavit was considered does not show that the court relied specifically on the position taken by John Schey. See App. Exh. R; Schey v. Johnson, Land Ct. Misc. Case. No 95 MISC 221634, Order (May 18, 2010). However, "[a]pplication of the equitable principle of judicial estoppel to a particular case is a matter of discretion." Otis, 443 Mass. at 640. Further, "judicial estoppel will normally be appropriate whenever 'a party has adopted one position, secure a favorable decision, and then taken a contradictory position in search of legal advantage." Id. at 641, quoting InterGen N.V. v. Grina, 344 F.3d 134, 144 (1st Cir. 2003). "[J]udges should use their discretion, and their weighing of the equities, and apply judicial estoppel where appropriate to serve its over-all purpose. That purpose is 'to safeguard the integrity of the courts by preventing parties from improperly manipulating the machinery of the judicial system,' and judicial estoppel may therefore be applied 'when a litigant is playing fast and loose with the courts.'" Id. at 642, quoting Alternative Sys. Concepts, Inc., 374 F.3d at 33 (internal quotation omitted).

In the previous litigation John Schey took the position that the door to the disputed area and the entire exterior area of the Schey house that near the disputed area and along the border with the Johnson property were almost never used after 1996 because they were blocked by the Johnson House. The Scheys succeeded in that previous litigation in getting the Johnson house removed. The Trust now argues the opposite point, that the use of the disputed area was substantial and continuous enough to give rise to a prescriptive easement. The two arguments are in direct conflict with each other. It appears that the Trust, now, after securing the removal of the Johnson house, has readily adopted a conflicting position where it will confer legal advantage in securing easements rights to the disputed area. The basis for the Trust's prescriptive easement claim is antithetical to the position espoused by John Schey in the earlier litigation. The court, exercising its equitable discretion, finds that the Trust is judicially estopped from asserting a claim for prescriptive easement.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, the Clarks' Motion for Summary Judgment is ALLOWED. Judgment shall enter declaring that the Scheys do not have an easement by prescription over the Clarks' property and dismissing the Complaint with prejudice.

SO ORDERED.

70 BUBIER ROAD TRUST, John Schey and Ruth Schey, Trustees, v. ROBERT CLARK, LESLIE CLARK, and U.S. BANK, N.A.

70 BUBIER ROAD TRUST, John Schey and Ruth Schey, Trustees, v. ROBERT CLARK, LESLIE CLARK, and U.S. BANK, N.A.